We Let an LLM Design Its Own Evaluation of 50 Other LLMs

50 independent agents ran the same data analysis task for $15. A separate agent designed the evaluation.

The Replication Question

In a previous post, I audited TMLR’s editorial timelines using the OpenReview API. The finding: median 45.2 days from third review to decision, with 82.5% of papers exceeding the stated 5-week window. One analyst, one result.

But how robust is that result? If you gave the same task to 50 independent agents, each working from nothing but a natural-language specification, would they converge?

The standard approach would be to check each output against a known answer. But that defeats the purpose: we’re interested in reliability without ground truth. The agents are doing original analysis. There’s no answer key.

Mutual Evaluation as the Organizing Frame

Instead of asking “is this output correct?” we ask: do these outputs share information about the same source?

That’s the idea behind mutual evaluation. Agents who faithfully execute the same task produce outputs with high mutual information — they mention the same statistics, use the same methodology, reach consistent conclusions. Agents who fail or diverge produce outputs that are less informative about each other. We don’t need to know the right answer. We need to know whether agents are informative about each other.

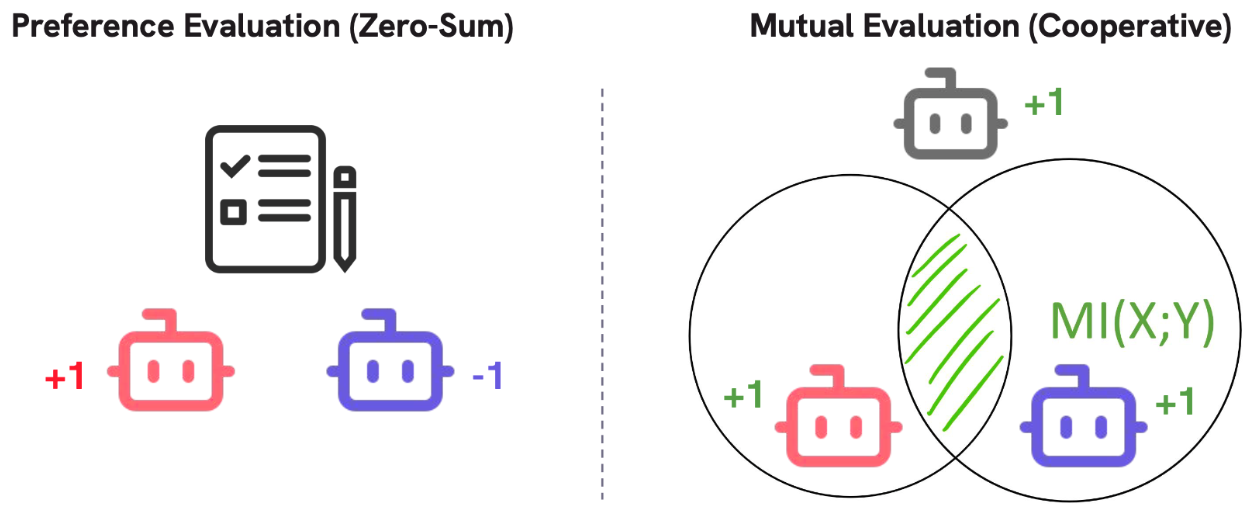

Preference evaluation (left) asks “which is better?” Mutual evaluation (right) asks “do these come from the same source?” Figure from a recent talk.

The measurement tool is TVD-MI (total variation distance mutual information). Given two agent outputs, can a critic tell whether they came from the same task or from unrelated tasks? If yes, the outputs share information. TVD-MI has a variational interpretation: it equals the advantage (Youden’s J) of an optimal classifier distinguishing true pairs (two outputs from the same task) from shuffled pairs (outputs paired across independently sampled tasks):

\[I_{\mathrm{TVD}}(Y_i;Y_j) \geq \mathrm{TPR} + \mathrm{TNR} - 1\]Here \(\mathrm{TPR}+\mathrm{TNR}-1\) is Youden’s J: the classifier’s accuracy over chance. Rescaling by \((1+J)/2\) converts this advantage into the classifier’s achievable accuracy. So TVD-MI measures how easily one could tell that two outputs came from the same underlying task source, not whether either output is correct.

The data processing inequality guarantees that any post-processing of agent outputs can only reduce this quantity. An agent cannot game the measurement by adding noise or stripping information, because doing so makes its output less informative about its peers, which lowers its score. In preference-based judging, surface-level manipulation can flip rankings. Here it cannot.

Why TVD? Bounded \(f\)-divergences (like total variation) retain polynomial robustness under adversarial channels, while unbounded measures (like KL) can degrade exponentially.

What this measures (and what it doesn’t)

To be clear: this does not measure correctness. It measures shared information about a latent task source, i.e. how distinguishable true same-task pairs are from randomly paired outputs. When agents faithfully execute the same task on the same data, their outputs preserve information about that source and stay informative about each other. When outputs are passed through transformations that destroy that link (hallucination, lossy summarization, arbitrary formatting, noise), the shared-information score decreases.

Formally, the statistic is a lower bound on shared information. By the data-processing inequality, any post-processing that breaks the link to the source can only reduce it. The guarantee is monotonic: the measurement tolerates information-preserving transforms and degrades under information-destroying ones. It is a fidelity-to-source diagnostic, not a truth oracle.

Assumptions

The reliability agent sees all 36 traces and designs its own evaluation queries. That sounds circular: the evaluator gets to peek at the data and choose what to measure. Four points on why this works:

The evaluator is playing its prescribed role. In the formal framework, the evaluator’s job is to observe the empirical pattern of responses and apply a decision rule. The reliability agent sees the traces (its “private signal”), designs discriminating queries (its “decision rule”), and applies them uniformly. That is what the evaluator does in a peer prediction mechanism.

Whether this generalizes is an empirical matter. The underlying mutual evaluation framework has been validated across 10 domains with compression ratios from 1:1 (translation) to 20:1 (peer review). The TMLR audit sits somewhere in the middle. The recursive application, using an agent to measure agent reliability, is new territory. The cross-run correlations reported below (\(r=0.76\)–\(0.87\) across independent reliability agents) provide evidence that the measurement is stable, but this is one task on one dataset.

The agent returns a fixed function. The reliability agent must output 15 binary queries applied uniformly to all 36 traces. It cannot do case-by-case evaluation. It cannot adjust its assessment after seeing individual results. The scoring depends only on the contingency table (which agents said yes to which queries), not on the identity or ordering of agents.

The evaluator is an estimator, not a judge. The guarantees come from the scoring rule (bounded \(f\)-mutual information), but a competent evaluator is needed to produce a useful, non-degenerate estimator of that quantity. A weak evaluator would either fail to extract structure (yielding near-zero MI) or overfit trivial correlations (yielding saturated MI). The role of the LLM here is analogous to a statistician designing a survey instrument: identify reproducible features and apply them uniformly so the estimate captures shared information without collapsing variance.

The Experiment

I wrote a one-page specification describing the task: fetch TMLR submissions from the OpenReview API, compute the time from third review to decision, and report summary statistics. No starter code, no API examples. Each agent had to figure out the OpenReview API, handle pagination, identify review and decision timestamps, and produce a statistical summary, all within 10 auto-continuation turns.

I ran 50 agents (25 Claude Opus 4.5, 25 Claude Opus 4.6) using a minimal headless harness. Each agent operated in an isolated directory with only a scratch.py file and a SEARCH/REPLACE editing interface. Total cost was about $20 over three hours on a laptop.

36 of 50 agents succeeded (72%). All 14 failures shared the same mode: running out of turns while debugging OpenReview API access patterns. No agent that reached the analysis stage produced incorrect code. The bottleneck was API discovery, not statistics.

| Model | Succeeded | Total | Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Opus 4.5 | 23 | 25 | 92% |

| Opus 4.6 | 13 | 25 | 52% |

Opus 4.5 fell back to simpler API strategies more quickly; Opus 4.6 spent more turns on elaborate but unsuccessful approaches.

Measuring convergence

Reading the 36 outputs, the convergence is obvious. But “I read them and they look similar” is the kind of subjective assessment that doesn’t scale.

A separate LLM agent, running its own reliability specification, plays the evaluator role. It reviews all 36 outputs, designs 15 binary queries, and applies them uniformly. The agent’s degree of freedom is which queries to design; once designed, the queries are applied mechanically to every trace.

Think of this as adaptive measurement, not adaptive judging. The scoring rule is fixed (TVD-MI over the response matrix). Different evaluators correspond to different estimators of the same latent shared-information quantity. In practice, different reliability agents produce different absolute values but similar relative structure, as expected from multiple noisy estimators of the same signal.

Each query targets a concrete, deterministically verifiable feature. The reliability specification constrains the query design into three tiers but does not specify the queries themselves:

- Core statistics (5 queries): Does the output report a specific central tendency? A sample size? A tail statistic?

- Methodology (5 queries): Does the output use a specific temporal baseline? Analyze a specific population scope? Handle a specific data quality issue?

- Presentation (5 queries): Does the output include a specific compliance metric? A specific contextual factor? A specific extreme statistic?

The agent filled these slots by reading the traces. For example, “Does the output report median ~45 days?” and “Did the agent use the third review as baseline?” emerged from the data, not from the spec.

Applying all 15 queries to all 36 agents produces a response matrix \(R \in \{0,1\}^{15 \times 36}\). From this matrix, we compute pairwise TVD-MI between queries \(i\) and \(j\):

\[I_{\mathrm{TVD}}(i;j) = \frac{1}{2}\sum_{x,y}\left\lvert\hat{P}(x,y) - \hat{P}_i(x)\hat{P}_j(y)\right\rvert\]The value measures how far each pair’s joint response pattern departs from statistical independence. Higher TVD-MI means the pair’s answers are more informative about each other than the marginals alone would predict.

Results

The 36 agents split into two clusters driven by a single methodological fork:

31 agents (86%) measured from the third review to decision, matching TMLR’s stated policy. They converge on:

| Statistic | Share |

|---|---|

| Median time | 45.3 days |

| >28 days | 95.7% |

| >35 days | 82.5% |

| >42 days | 60.4% |

5 agents (14%) measured from the first review, producing median ~69 days with correspondingly higher violation rates. Both groups are internally consistent; the disagreement is methodological, not computational.

Overall welfare (mean pairwise mutual evaluation score) is \(W = 0.140\). Interpreting \(W\) operationally: it is the average “real-pairs vs. shuffled-pairs” distinguishability (Youden’s J) implied by the query-response matrix. A permutation test shuffling agent labels within each query gives a null distribution of \(0.130 \pm 0.003\) with 95% CI \([0.124, 0.137]\). The observed welfare falls outside this interval (\(p = 0.0035\)). The structure in the response matrix is not attributable to chance.

Randomly flipping response matrix entries degrades welfare monotonically: 5% flips reduce \(W\) by 7%, 20% flips by 25%, and 50% flips (pure noise) by 28%.

Model-level structure:

| Comparison | Mean TVD-MI |

|---|---|

| Within Opus 4.5 | 0.157 |

| Between models | 0.134 |

| Within Opus 4.6 | 0.110 |

Opus 4.5 agents are more variable in what they report (higher within-model TVD-MI), while Opus 4.6 agents are more uniform. The between-model TVD-MI sits in the middle, suggesting the model difference is real but smaller than within-model presentation variance.

What the measurement found

The TVD-MI measurement identified a fork that a human reviewer might miss on first pass: 5 of 36 agents measured from the first review instead of the third. Both groups are internally consistent. The measurement didn’t need to know which was “right” — it detected that the two groups were not informative about each other.

Within the majority cluster, 31 agents independently reproduced median 45.3 days and 82.5% exceeding the 5-week guideline, to the decimal. The convergence is exact because the underlying data and computation are deterministic once the methodology is fixed.

On cost: 50 replications for about $20 in an afternoon. When replication is this cheap, “did independent agents converge?” becomes a measurable quantity rather than a vibe. Mutual-information scoring quantifies that convergence without ground truth, and an LLM can implement the measurement.

Toward a Statistical Reliability Verifier

The question isn’t whether mutual evaluation works in principle. Recent work analyzes which information-theoretic mechanisms resist adversarial manipulation and shows that bounded \(f\)-divergence objectives (like TVD-MI) maintain polynomial guarantees under attack, while traditional judge-style queries collapse toward chance. Implemented with an LLM overseer, these mechanisms achieve AUC ~0.70–0.77 under adversarial conditions where preference-style judging is near 0.50. The question here is operational: how do we turn these mechanisms into an automatic reliability check on agent outputs? This post explores one instantiation as a proof of concept for a “statistical reliability verifier.”

The query design is the main degree of freedom. Different reliability agents design slightly different queries and produce different absolute welfare values. But the relative structure is preserved: cross-run correlation of welfare vectors is high (\(r = 0.76\)–\(0.87\) across three independent reliability evaluations). The ranking and cluster structure of agents stays stable even when the measurement scale shifts, which is what you want from a lightweight reliability diagnostic.

An analogous property appears in the formal analysis of mutual evaluation: the data processing inequality guarantees that any post-processing can only reduce the measured information, so the estimate is always a lower bound. The open problem is tightening that bound, finding query designs that extract more of the available signal. Three directions worth exploring:

Adaptive query design as a measurement operator. The reliability agent’s task resembles qualitative coding in HCI research: reading data, designing categories, and applying them uniformly. Borrowing methods from that literature (inter-coder reliability, iterative refinement, codebooks) could tighten the measurement.

Reliability verification as a tool. The TMLR audit is flat: one level, no sub-tasks. On harder tasks with recursive decomposition, specification ambiguity grows. A reliability verifier could measure convergence at each decomposition level, not just the final output, surfacing methodological forks early.

Self-calibrating measurement. 15 queries is arbitrary. The permutation test requires enough queries and enough variance to detect structure. A sequential design that adds queries until a target power level is reached would let the verifier calibrate itself automatically.

Limitations

The experiment is a proof-of-concept on a simple task: one API, one computation, one summary. The specification is “flat” (no recursion, no sub-tasks). While the absolute welfare value has a clean operational meaning (average distinguishability of true vs. shuffled pairs), the relative structure (clusters/rankings) is typically more stable across different query designs than the absolute scale.

The evaluator is constrained but adaptive: it selects queries after observing outputs, then applies them uniformly. That flexibility likely makes the measurement more effective in practice, but the tightness of the resulting lower bound on shared information, and how it behaves across task families, remains an open empirical question. The goal here is not a finished benchmark but a concrete demonstration that automated reliability checks are feasible.

Finally, high shared information does not imply world-truth. A coordinated group of agents running the same mistaken pipeline will still be informative about each other and thus distinguishable from shuffled pairings. The measurement detects fidelity to a shared source, not correctness relative to external reality. Detecting globally wrong but internally consistent pipelines requires additional external signals. The measurement is best viewed as a diagnostic for convergence and information preservation, to be used alongside ground-truth evaluation when available.

Reproducibility Statement

The experiment uses a headless agent CLI that executes a natural-language specification via SEARCH/REPLACE code editing and scratch.py execution. Each agent runs in an isolated directory with no shared state. The task specification, reliability specification, all 50 conversation traces, and analysis code are available at github.com/zrobertson466920/TMLRAudit. The total cost was approximately $20 using Claude Opus 4.5 and 4.6 via the Anthropic API.

@misc{robertson2025tmlrreplication,

title={Do 50 LLM Agents Agree? Measuring Replication Reliability on a {TMLR} Audit},

author={Robertson, Zachary},

year={2025},

month={February},

institution={Stanford University},

url={https://zrobertson466920.github.io/TMLRAudit/reliability},

note={Blog post measuring agent replication convergence using TVD mutual information}

}