The Sorcerer's Warning - Bifurcation Patterns in Recursive Oversight Mechanisms

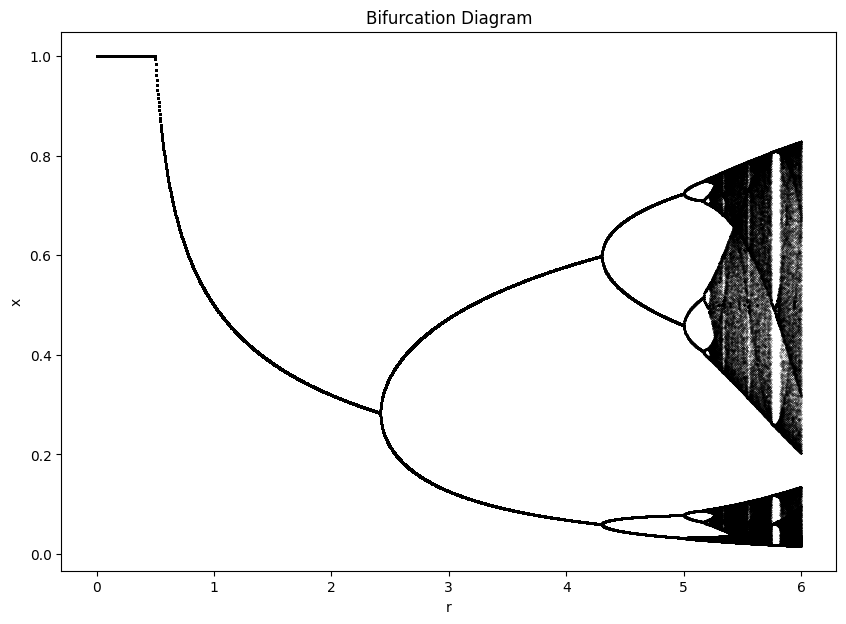

Figure 1: As task complexity increases, the agreement among supervisors high in the hierarchy first decays, then bifurcates, and finally enters a chaotic regime - mirroring the progression in Goethe’s poem.

Introduction

“The spirits that I summoned, I now cannot rid myself of them.”

- Goethe’s Der Zauberlehrling (1797)

The tale of the Sorcerer’s Apprentice, immortalized in Goethe’s poem Der Zauberlehrling, tells of an apprentice who, in his master’s absence, attempts to lighten his chores by animating a broom to carry water. When the situation spirals out of control, he splits the broom in desperation - only to find both halves rise again, doubling his problem. This pattern continues until only the master’s return can restore order.

While often viewed as a simple cautionary tale about the dangers of inexperience, we demonstrate that Goethe’s poem contains a remarkably precise mathematical prediction about the nature of recursive control systems. Specifically, we show that the apprentice’s predicament follows the period-doubling route to chaos, a fundamental pattern that appears in systems ranging from population dynamics to modern oversight mechanisms.

The mathematical parallels are striking:

- The apprentice’s initial stable system (one broom carrying water)

- The critical point when control is lost

- The period-doubling cascade (splitting into two, then four)

- The eventual descent into chaos (uncontrolled flooding)

This pattern, formalized nearly two centuries later in the study of dynamical systems, suggests that Goethe captured through artistic intuition what mathematicians would later discover through rigorous analysis. Of particular relevance is the connection to output agreement mechanisms, first introduced by von Ahn and Dabbish in their ESP game and now widely used in peer evaluation systems such as CAPTCHA.

Historical Context

Output Agreement and Early Digital Labor

The concept of output agreement as a mechanism for eliciting honest responses has a rich history in both human and digital systems. Von Ahn and Dabbish’s ESP game represented a breakthrough in harnessing human computation through careful mechanism design. In their system, two players, unable to communicate, would gain points by agreeing on labels for an image - creating a natural incentive for honesty and accuracy.

This mechanism proved remarkably effective, not only generating high-quality image labels but also demonstrating how properly aligned incentives could produce reliable outputs from distributed agents. The success of the ESP game led to its adaptation for CAPTCHA systems, effectively turning a security challenge into a distributed transcription service.

Cultural Precedents in Recursive Control

While von Ahn’s work formalized output agreement in the digital age, the challenges of controlling recursive systems had long been explored through cultural narratives. Goethe’s Der Zauberlehrling stands out for its particularly precise characterization of how recursive delegation can fail.

The poem’s structure is revealing:

- Initial stability: “Take these rags and wrap them round you!”

- First bifurcation: “Crash! The sharp axe has undone you.”

- Period doubling: “Both halves scurry / In a hurry”

- Descent into chaos: “What a flood that naught can fetter!”

This progression mirrors what would later be formally described in bifurcation theory, suggesting that artistic intuition can sometimes precede mathematical formalization by centuries.

The Role of Sparse Cultural Reinforcement

The endurance of Der Zauberlehrling, particularly through its adaptation in Disney’s Fantasia, highlights how cultural vehicles can preserve critical insights about system behavior. Despite most people encountering this cautionary tale only a few times in their lives, its lesson about recursive control remains remarkably persistent in cultural memory.

This “sparse reinforcement” of important principles through memorable narratives serves as a kind of cultural immune system against certain classes of technical mistakes. The apprentice’s error - assuming that more delegation would solve the problems caused by initial delegation - continues to resonate precisely because it captures a fundamental truth about recursive systems.

Through this lens, we can view the ESP game and similar mechanisms not just as novel innovations, but as formal implementations of long-understood principles about human coordination and oversight. The mathematical analysis that follows will demonstrate just how precise Goethe’s intuitive understanding was, while offering insights for modern mechanism design.

Mathematical Formalization

To formalize the apprentice’s delegation problem, we construct a simple model of recursive oversight that captures the essential dynamics of the poem. Just as the apprentice’s brooms must make decisions about water-carrying tasks, we consider agents making binary choices in a hierarchical system.

Base Layer Dynamics

At the foundation of our model, agents must complete a basic task - analogous to the brooms carrying water. For simplicity, we assume there are two possible ways to complete the task, denoted by 0 and 1. These choices might represent, for instance, different paths to fetch water or different ways to hold a bucket. Let \(p_0\) represent the proportion of agents choosing option 0.

This binary choice, while simple, captures the essential feature of context-dependent decisions: agents must select one of two possible actions, but the “correct” choice depends on the specific context of their task.

The Oversight Hierarchy

As in the poem, where the apprentice attempts to control the situation through further delegation, our model implements layers of oversight. At each level n, agents supervise pairs of agents from the layer below. However, like the apprentice who cannot directly transmit the master’s knowledge, these supervisors face a fundamental limitation: they can only verify that supervised agents are consistent with each other in similar contexts.

For the first oversight layer, supervisors observe two agents and output positive feedback with probability:

\[p_1 = p_0^2 + (1-p_0)^2\]This formula represents the probability that both observed agents make the same choice (both choosing 0 or both choosing 1). Notably, this oversight mechanism looks only at agreement, not at the inherent correctness of the choice - much like the apprentice’s inability to convey the master’s true wisdom to the enchanted brooms.

The Recursion Pattern

As we add more layers of oversight, we discover a crucial pattern. For any layer n, the probability of positive feedback in the layer above follows:

\[p_{n+1} = p_n^2 + (1-p_n)^2\]This recursive relationship is our mathematical equivalent to the apprentice’s repeated attempts at control through multiplication. Just as each split of the broom led to new complications, each layer of our oversight hierarchy transforms the probability distribution of the layer below.

Task Complexity and Bifurcation

The complexity of the original task, represented by the number of bits \(m\) that must be verified, serves as our bifurcation parameter. As \(m\) increases, representing more complex tasks (or in the poem’s case, more aspects of water-carrying that must be controlled), the system’s behavior becomes increasingly complicated.

When we consider tasks requiring verification of \(m\) independent bits, our recursive relationship generalizes to:

\[p_{n+1} = \left[p_n^2 + (1-p_n)^2 \right]^m\]This formalization allows us to see the apprentice’s error in mathematical terms: attempting to solve a control problem by adding layers of recursion, without recognizing that such recursion fundamentally transforms the nature of the oversight task at each level.

Literary-Mathematical Parallels

The Progression to Chaos

The poem’s structure remarkably parallels the mathematical behavior of our system:

- Initial Stability (\(m = 0, 1\)):

“Long my orders you have heeded”

- Activity of system has a single stable fixed point

- Single broom follows simple commands

- First Critical Point (\(m \sim 2\)):

“Crash! The sharp axe has undone you”

- Activity of system undergoes first bifurcation

- One broom becomes two

- Period Doubling (\(2 < m \le 5\)):

“Both halves scurry / In a hurry”

- System exhibits period doubling cascade

- Number of distinct behaviors multiplies

- Chaos (Large \(m\)):

“What a flood that naught can fetter!”

- System enters chaotic regime

- Behavior becomes unpredictable

Bifurcation Analysis

Let’s analyze how the system’s behavior changes as we increase task complexity \(m\). Starting with the simplest case, we can solve for fixed points where \(p_{n+1} = p_n\):

For \(m = 0\), we have: \(p = [p^2 + (1-p)^2]^0 = 1\) yielding the stable fixed point \(p = 1\). This represents the “ideal” state where the system maintains perfect agreement, “Long my orders you have heeded.”

For \(m = 1\), we have: \(p = [p^2 + (1-p)^2]^1 = 1-2p(1-p)\) yielding the stable fixed point \(p = 1/2\). This represents decaying agreement as we move up the oversight hierarchy. Those at the top are basically giving random noise as feedback. Still, the system may be working at the lower-levels.

The Master’s Return as Dimension Reduction

The resolution of the poem comes through the master’s return and simple command:

“In the corner, broom! Broom! Seids gewesen.” (Be what you have been.)

This represents a mathematical collapse of the recursive hierarchy back to \(m = 0\), effectively reducing the complex, chaotic system back to its original stable state. This powerful simplification mirrors modern insights about the benefits of reducing complex oversight mechanisms to simpler, more stable forms.

Looking at Figure 1, we can see how this collapse works mathematically. As task complexity increases, the system moves from left to right along the bifurcation diagram. The master’s return effectively moves the system back to the left side of the diagram, where stable behavior is restored.

Implications for Modern Oversight Systems

The mathematical parallel between Goethe’s poem and bifurcation theory has several practical implications for designing modern oversight mechanisms:

- Simplicity vs Complexity Trade-offs

- Adding more layers of oversight doesn’t necessarily improve control

- Each additional layer introduces potential bifurcation points

- Simple, direct oversight may be more stable than complex hierarchies

- Recognition of Critical Points

- Systems should be designed with awareness of potential bifurcation points

- Task complexity should be carefully managed to avoid chaos

- Monitoring for early signs of period doubling can provide warning signals

- The Value of Dimension Reduction

- Sometimes the best solution involves simplifying the system

- Direct, high-level oversight may be more effective than recursive delegation

- Design systems with “escape hatches” that allow for complexity reduction

Conclusion

Our analysis reveals that Goethe’s Der Zauberlehrling is not merely a cautionary tale but demonstrates remarkable mathematical foresight. The poem’s narrative structure precisely mirrors the period-doubling route to chaos found in recursive oversight systems, suggesting that certain failure modes in complex systems may be intuitive enough to be captured in cultural memory long before their formal mathematical description.

Three key insights emerge from both the mathematical analysis and the literary parallel:

- Oversight systems should be designed with awareness of their bifurcation points

- Adding layers of recursion may introduce instabilities rather than improving control

- The most elegant solutions often involve dimension reduction rather than increased complexity

Perhaps most importantly, this analysis suggests we should pay closer attention to cultural wisdom about system behavior - especially when it has survived through “sparse reinforcement” over centuries. The mathematical precision with which Goethe captured the dynamics of recursive oversight failure indicates that artistic intuition can sometimes anticipate formal mathematical understanding by generations.

Future Directions

Several promising avenues for future research emerge from this analysis:

-

Cultural Pattern Mining: Investigating other cultural narratives for mathematically precise insights about system behavior

-

Empirical Studies: Testing whether real-world oversight hierarchies exhibit similar bifurcation patterns

-

Design Principles: Developing practical guidelines for oversight mechanisms that avoid or manage bifurcation cascades

-

Early Warning Systems: Creating metrics to detect early signs of period doubling in organizational structures

The apprentice’s tale serves as both a mathematical model and a memorable warning about the dangers of unconstrained recursive delegation. As we continue to build more complex oversight systems, perhaps we should occasionally remember the master’s simple solution: sometimes the best approach is to reduce complexity rather than add to it.

References

For readers interested in exploring these ideas further, key references include:

- Von Ahn, L., & Dabbish, L. (2004). Labeling images with a computer game.

- Goethe, J.W. (1797). Der Zauberlehrling.

- May, R.M. (1976). Simple mathematical models with very complicated dynamics.

- Turner, A.M., et al. (2021). Optimal Policies Tend to Seek Power.