(Re)search - How to Grow A Tree in the Garden

When I first conceived the Branching Directive, I imagined tending a garden of knowledge, guided by Voltaire’s famous advice to “cultivate our own garden.” What I discovered instead was a tree – one that grows according to attachment patterns found throughout nature. This perspective transforms my understanding of how research and knowledge naturally organize themselves.

From Garden to Tree

The growth is driven by a simple attachment process:

- An entry is written

- A link is made to a previously written entry

- While alive repeat (1 \( \to \) 2) OR (2 \( \to \) 1)

While it is a simple growth process it has allowed for a variety of research to be conducted. After five years of development, my research management system has evolved into something far more intriguing than I initially imagined. The system, which is human research, has grown to contain millions of tokens of text across thousands of interconnected entries. But the most fascinating discovery came when I analyzed its structure.

Structure and Growth

Analyzing my research tree revealed two major “groves” of knowledge:

- A philosophical core (312 entries) containing foundational concepts

- A larger section (3,649 entries) with detailed reflections and research content

Time-lapse visualization showing how my research tree grew over time, with new branches forming and connecting as knowledge accumulated.

Just as a tree develops through seasons, my research showed distinct growth patterns. I observed what I call “foliation periods” – times when new entries sprouted rapidly in multiple directions before settling into more organized structures. This mirrors how trees first produce leaves in seemingly chaotic patterns before organizing them for optimal sunlight exposure.

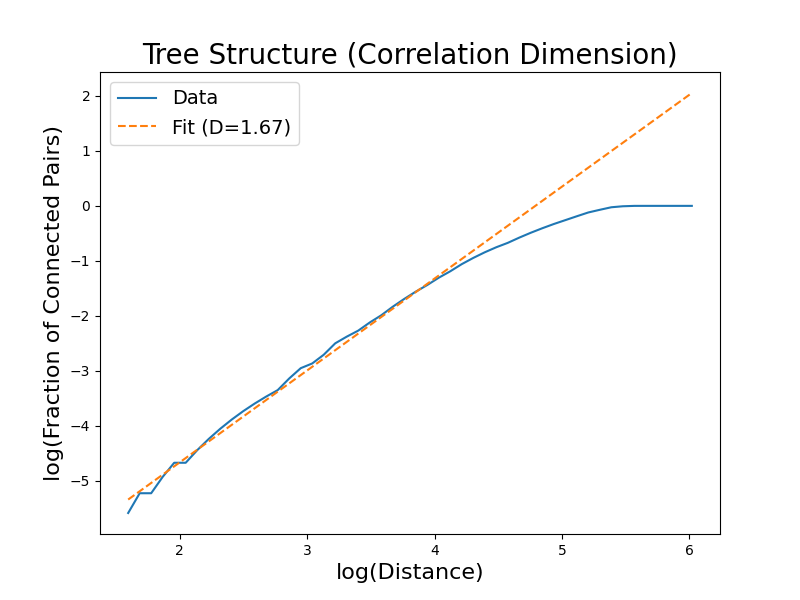

Scientists try to measure or quantify self-organization using something called the correlation dimension. On the x-axis I measure the logarithmic distance between nodes in the tree - how many steps you can take moving from a start node. On the y-axis I plot how many randomly sampled pairs in the tree are within the distance specified on the x-axis and then take the logarithm.

The correlation dimension plot reveals a striking pattern: my research tree grows with a fractal dimension of 1.67, similar to patterns found in natural branching structures.

To understand this graph, imagine zooming into a tree’s branches. At each level of magnification, you see a similar pattern repeated – larger branches splitting into smaller ones. A straight line has a dimension of 1, while a filled plane has a dimension of 2. Natural branching patterns, like those found in trees, lightning, or river networks, often fall between these values.

This research tree shows exactly this kind of natural branching, with a correlation dimension of 1.67 (± 0.07). This isn’t just a curious coincidence – it suggests that knowledge organization, when allowed to grow naturally, follows patterns similar to those found throughout nature.

Research Applications

This growth pattern has several implications for how I think about knowledge organization. Traditional knowledge bases are often designed with rigid hierarchical structures. These findings suggest that allowing more organic growth patterns – similar to how trees branch or lightning spreads – might be more effective.

I hope to use this as a benchmark for studying:

- Natural knowledge organization patterns

- Integration of AI assistance in research

- Long-term knowledge accumulation

- Self-organizing information structures

Towards this goal, I am preparing to release a sanitized version of the research forest (approximately 650,000 tokens) as a benchmark dataset. This will allow others to:

- Study natural knowledge organization patterns

- Test AI research assistance systems

- Develop new metrics for measuring knowledge structure

- Explore the parallels between natural and artificial information growth

Just as ecologists study trees to understand natural systems, I believe studying how thought naturally organizes itself can lead to better ways of managing and growing information. My research has evolved from tending a simple garden to understanding a complex tree ecosystem, complete with its own natural laws and patterns.

We invite researchers and developers to consider: How might understanding these natural patterns of knowledge organization influence the design of future information systems? Could artificial chains of thought be more effective if they had features more resembling self-organized branching structure?

As I continue to explore this frontier where human knowledge meets artificial intelligence, I’m reminded that sometimes the most profound insights come from simply observing and understanding the natural patterns that emerge when we let knowledge grow.